Saturday Night was Cruiser’s Dinner at RYC, a frequently held event where the very jovial group of cruisers at RYC get together for dinner. It’s a jolly and fairly liquid affair, often accompanied by a talk on something or other. This Saturday, the something or other was “Rigging Tips” given by David Thompson from John Eggers. Eggers is a local sail-maker and rigging specialist. There aren’t many businesses like these guys left and they have a great reputation. After listening to David for a couple of hours I can see why.

David is the kind of guy I am in awe of. He lives sailboats. The guy could wax lyrical about esoteric boat part names like strap tangs, the pros and cons of different cotter pin types and the benefits of wire rig over rod rig for hours. In fact he did so, much to the chagrin of some of the dinner guests who could only take so many insights about the dangers of corrosion on boom-stays. I hung on every word.

I took notes on everything I could and over the next few weeks I will post tips that David shared every Monday till I run out of them. I will start with the basics and I asked the most basic of question, which was patiently tolerated by the experienced cruisers around me, specifically, What Are The Basics of Tuning The Rig?

This is motherhood and apple-pie to most sailors but I found David’s answers a good refresher that connected the dots for me. David divided tuning into two parts: Tuning fore and back-stay for helm balance, secondly tuning the shrouds for mast position and rig tension.

First as an aside, a definition of weather helm as found on wikipedia:

While it is true that an increased angle of heel generally increases

weather helm, it is misleading to identify heel as the cause of

weather helm. The fundamental cause of “helm”, be it weather or lee, is

the relationship of the center of pressure of the sail plan to the center of lateral resistance of

the hull. If the center of pressure is astern of the center of lateral

resistance, a weather helm, the tendency of the vessel to want to turn

into the wind, or to weather-vane, will result. A slight amount of

weather helm is thought by many skippers to be a desirable situation,

both from the standpoint of the “feel” of the helm, and the tendency of

the boat to head slightly to windward in stronger gusts, to some extent

self-feathering the sails. It also provides a form of dead man’s switch—the boat stops safely in irons if

the helm is released for a length of time.If the situation is reversed, with the center of pressure forward of

the center of resistance of the hull, a “lee” helm will result, which is

generally considered undesirable, if not dangerous. Too much of either

helm is not good, since it forces the helmsman to hold the rudder

deflected to counter it, thus inducing extra drag beyond what a vessel

with neutral or minimal helm would experience.

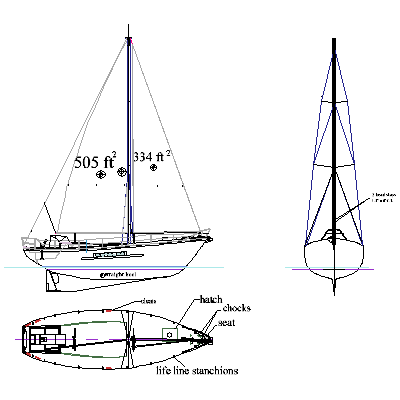

You adjust for weather and lee helm by shifting the rig forward or aft by adjusting the back-stay and fore-stay, i.e. to counter weather helm you loosen the back-stay and tighten the fore-stay, shifting the force of the sails forward balancing the boat. You adjust for lee helm by moving the rig backward.

I have to say that I am still wrapping my head around back-stay adjustments. When you are racing, you tighten the back-stay to add twist, flatten the sails and reduce heel. I can only assume that the reduction in heel and pressure induced by a tighter back-stay and flatter sails has a greater affect than the additional weather helm created by shifting the rig and center of pressure aft. (Suggestions anyone?)

The second part of tuning is related to stability and position of the mast. First you want to make sure that the mast is straight. The easiest way to do this is when the boat is at rest and preferably flat, lie at the foot of the mast with an eye up the mast. You should be able to tell if it’s out of whack this way. If you want to be absolutely sure, use your halyard to run a tape measure up the rig, checking very precisely the length of each stay. If stays on one side are longer than the other you know that you need to adjust the stays accordingly to straighten the column of the mast.

To see if the stays are correctly tightened test them when you are under sail in a moderate breeze (10-12kts) by checking the slack in your leeward shrouds. If there is no slack, they are too tight. Loosen the leeward shrouds 1-2 turns or until they have a bit of give, then make the identical adjustment on the windward side (This is important, if you don’t make the same adjustment on the windward side your mast column will be out of whack). Equally, if your leeward shrouds feel too slack (by this I mean a little flappy), tighten them 1-2 turns, again making the same adjustment to windward. You may need more turns to get the rig appropriately tight but David was suggesting doing it in 2 turn increments.

Et voila!

Suffice to say, I am wide open to correction of inaccuracies or better tips.

I have read this argument about fore-and-aft sail balance controlling weather helm for so many years and from so many knowledgeable experts that I concede it must be true. After all, those are the guys who are out there winning races.

I also must conclude that I live in some sort of parallel universe where what is true in the real world doesn’t apply to me. I do know that I can sail my Catalina 30 under jib alone with no noticeable lee helm and that, when the wind pipes up and the boat really starts to heel, I’ll have quite a nice weather helm, even without the main. In my bizarro world, it certainly seems like most of my boat’s weather helm is attributable to heeling.

Years of confusion have also left me with these other foggy notions:

– Adjusting backstay tension follows different rules depending on whether you have a fractional rig.

– Increasing backstay tension on a fractional rig will induce mast bend that will, in turn, flatten the main, and most fractional rigs therefore usually have tapered masts that are designed to bend easily.

– On a mast head rig, though, more backstay mainly increases jib luff tension – a good thing if your jib luff is curving away to leeward.

I’m probably wrong about all of this, but I’ve become comfortable with my delusions over the years, and I’m too old to change now.

Also unique to a Catalina 30 is the backstay’s ability to widen the crack that usually develops on the bottom of the boat between the keel stub and the keel proper. Those who increase the boat’s usual 4:1 or 8:1 purchase on the backstay adjuster to a more manly 16:1 usually end up paying the price in yard bills the next time their boat is hauled.

The backstay adjuster is a nice place to mount a video camera, though.

One of the reasons I love blogging is getting comments like this.

The joy and frustration of sailing is nothing is simple.

Some thoughts:

1. The old theory about weather helm was that it was the hull lying more in the water caused by the heel that created weather helm. Your experience would bear that out.

2. I wonder of the fact that the mast is quite a ways forward and you may have a big genoa has something to do with the way your boat sails on the genoa only as the center of effort is quite forward

3. Buggered if I know.

God I love sailing

On the Etchells, in heavy air, tightening the backstay reduces weather helm, rather than increasing it. That’s one of the many strings I can pull to depower if things get hairy — Etchells don’t reef, but they have a whole lot of other options. One option for depowering that doesn’t always work well is dropping one of the sails — that sometimes results in the boat going backwards.

A friend with a Knarr told me the same thing. I was surprised to learn the main had no reef points. But, like the Etchells, the rig is fractional and the mast is made to bend quite a lot.

Here’s a photo of an Etchells that shows the mast bend (especially above where the forestay attaches) and you can see how flat that makes the main:

http://www.etchells.org.au/news/images-photos/Cronulla_No_Mercy_Audi_Etchells_Worlds.jpg