One of my greatest passions in life is sailing. I didn’t sail growing up and very few of my friends or family sailed so I am not really sure where the interest came from. Early in our marriage, my wife and I decided that it would be good to have a common interest. Neither of us liked golf and both of us were intrigued by sailing. We took some lessons and bought a small boat that we could sail on Galveston Bay. We loved it and it has been a shared passion that bonds us.

One of my greatest passions in life is sailing. I didn’t sail growing up and very few of my friends or family sailed so I am not really sure where the interest came from. Early in our marriage, my wife and I decided that it would be good to have a common interest. Neither of us liked golf and both of us were intrigued by sailing. We took some lessons and bought a small boat that we could sail on Galveston Bay. We loved it and it has been a shared passion that bonds us.

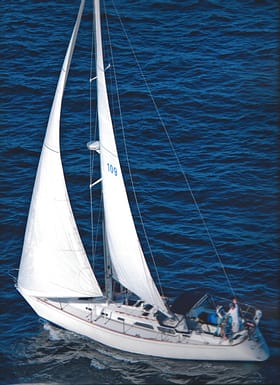

Over thirty-three years, we have sailed in many places, on multiple types of boats, and in many conditions. We have sailed up and down the Atlantic coast, Texas, Southern England, Turkey, all over the Caribbean, Hawaii, and even on Lake Dillon in the Rockies. We have owned three boats, the last was Cadence, a 38-foot sloop, we sailed from 2010 to 2019. We kept her in New Jersey initially and then mostly in New England, with Newport RI, as her base.

Scratching an Itch

I calculated that I have personally sailed over 5,000 miles. It’s the equivalent of sailing from the US to the UK.

However, this was done in 20-mile increments. Despite all this experience, I have never sailed offshore more than 20 miles. It’s actually not that unusual, as many sailors have not experienced offshore sailing and limit their sailing to coastal and lake sailing. And this is with good reason. Offshore sailing is much more challenging.

I felt like an incomplete sailor, especially as many of my sailing friends had sailed offshore and some extensively. It has been a personal goal to sail a big distance and, take part in the biennial Newport RI to Bermuda Race.

Why Offshore Sailing is Different

Coastal or Inshore sailing is not without risk. There are many ways you can get in trouble sailing along a coast and conditions can get scary five miles from land, but offshore sailing takes this to a new level of scary.

The basic difference is how long you sail. Coastal sailing passages are typically during daylight and last less than 12 hours (occasionally a full day). Most of our coastal passages were 20 miles and occasionally more than 100 miles with stops along the way. We rarely sailed Cadence in darkness.

Offshore passages last for several days and nights. The Newport-Bermuda passage is typically 4 to 5 days long. The Transpac typically takes 12-14 days to sail from California to Hawaii. Crossing the Atlantic can take 2 to 3 weeks.

And that means sailing continuously, through the night and regardless of how the weather forecast changes. And over that period the weather forecast will most likely change.

Waves can be enormous offshore. Think about looking behind you and seeing a 25-foot wave towering over you. If the forecasted waves are big and you are a coastal sailor, you won’t leave the dock. If you are sailing offshore and the waves build from 3 feet to 10 feet, you just have to deal with it.

If the wind forecast is for over 20 knots (kts) with a possibility of gales later in the day, most coastal sailors stay home. If you are sailing close to shore and conditions exceed the weather forecast, you can head for a safe harbor. Offshore sailors have to tough it out.

In coastal sailing, if you get in trouble, you can radio the coast guard and they will come to your assistance. If you are 200 nautical miles (nm) offshore, you are most likely out of range of a helicopter. A coast guard vessel could take days to get to you and the nearest ship may not be able to assist you. You may be on your own, so you plan accordingly.

And things can go wrong. Tragically, in this recent Bermuda Race, a sailor I knew was washed overboard and died as the crew was attempting to recover him. This sailor was highly experienced, well-prepared, and had a great crew, some of whom I have known for years. Fatal accidents can happen to anyone.

An Opportunity, A Big Disappointment, Then Delight

For a reason that I can’t explain I have yearned to sail offshore for decades. A great friend, Phil Asche is a highly experienced offshore sailor who has sailed tens of thousands of miles, much of this on Freebird, his Swan 44, a well-built and meticulously maintained yacht.

For a reason that I can’t explain I have yearned to sail offshore for decades. A great friend, Phil Asche is a highly experienced offshore sailor who has sailed tens of thousands of miles, much of this on Freebird, his Swan 44, a well-built and meticulously maintained yacht.

He had entered the 2022 edition of the Bermuda Race and asked me if I wanted to crew with him. I leaped at the opportunity.

Unfortunately, less than a week before the race start, I tested positive for COVID. Although I had no symptoms this made me a risk to the crew. Moreover, every race participant had to be tested within 72 hours of the race and testing positive would make me ineligible to race.

I dropped out and I was gutted.

I glumly stayed in touch with Phil and the crew as they prepared and tried to console me. I was letting them down too as they would now only be sailing with a crew of four, three of whom were in their 70s.

I tracked their passage obsessively, through the race website, and kept up with conditions. They had a tough race as winds were 20+ kts with significant waves. Some equipment issues slowed them down too. They finished in 5 days and ahead of several comparable boats but not up on the podium.

Three days into the race, when they were still over 150 days from Bermuda, I received this text from Phil via their Iridium Satellite system.

I can’t share my response, but it was strongly in the affirmative. While it was still disappointing not to take part in the race, I would be sailing over 600 miles offshore, crossing the Gulf Stream, and sail into Newport, RI, a town that I hold dear.

In Part 2, I will tell you about the boat and the crew.